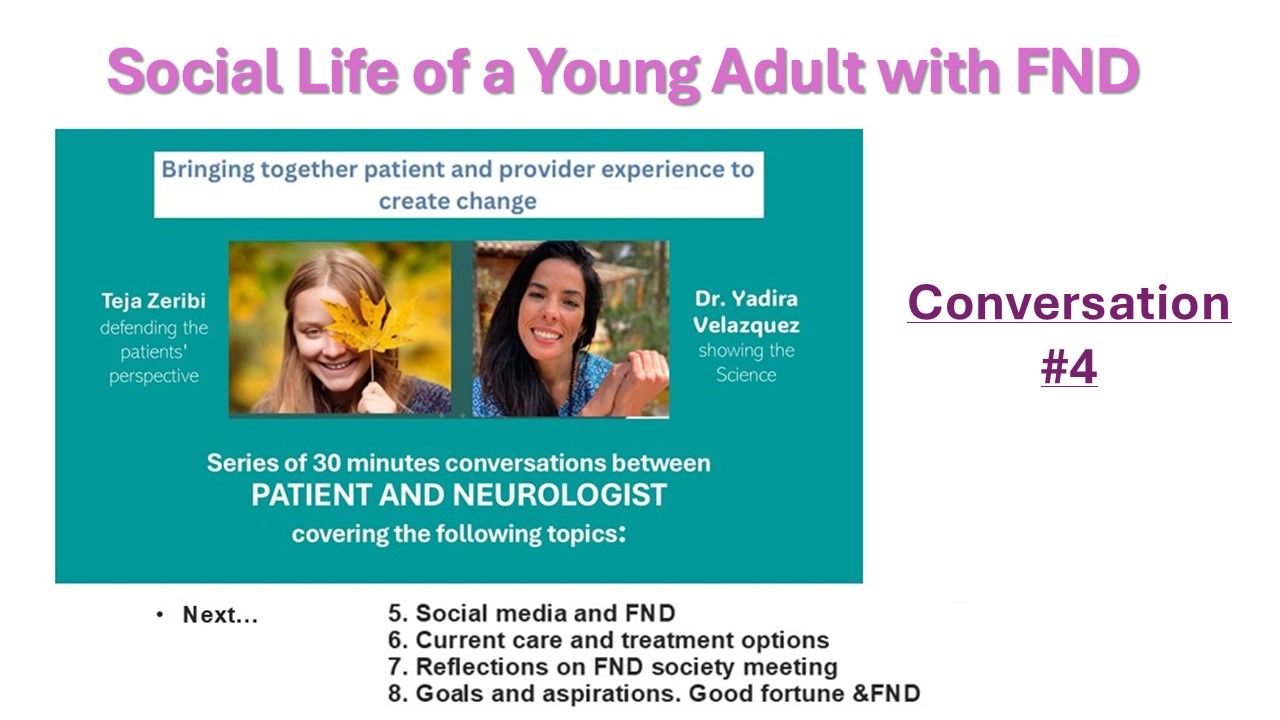

Patient - Provider Experience Series: Talk #4: Social life of a Young adult with FND - w/ Dr. Velazquez and Teja Zeribi

Jul 12, 2025

Watch video interview here

Teja Zeribi:

I honestly feel a significant amount of hypocrisy writing this. The honest preface I feel obligated to write is that while I have experienced social stigma due to my FND, certainly affects, most of it has been independent of the diagnosis and related to the presentation of seizures rather than having FND. Which has historically been intentional. Very few people in my interpersonal life -independent of my parents, know what FND means to me (or perhaps even what it is), the extent it impacts me, or what treatment looks like for me. I do not like to feel defined by it, so classmates I interact with daily don’t know I have it. Some know I have functional seizures or seizures, but don’t know why, how that is different from epilepsy, or that it is part of a much broader diagnosis. Best friends never asked for more information than I was willing to share, which was often just “I’ve been diagnosed with FND” or “I have functional seizures”, even if they witnessed and managed seizures.

They didn’t ask what it was, my treatment, etc. unless I shared, which was rare if ever. This is ironic and certainly a dichotomy considering the impact it has had on my life -and also my current life, while less influenced by symptoms, certainly is heavily influenced by FND. I easily work 10 hours every week in research or peer support, often much more, but to my friends' impression, it is a research side job that makes sense for a pharmacy student, not a deeply personal role that holds much more weight than a part time job. It is one of the most fulfilling parts of my week -especially the weeks we have a synchronous peer support group, and yet few people know that.

I want to make it clear -I have never lied about my diagnosis, asked for unnecessary medical treatment should I have a seizure, and would always tell people it was FND or a functional seizure -but I would never elaborate on what that meant. I knew they would likely google it, which worried me given misinformation, or even ambiguous information, and lack of room for clarification on my part, but I let them do what they wanted and didn’t disclose anything more.

It sometimes feels like this piece of me I get to hold onto, and protect, because for better or worse, I know it will impact how people will see me. I think I am starting to realize that it should. It does impact me. It doesn’t have to impact their perception of me negatively -and I think true friends would realize how much stronger of a person I am because of my FND. But the fear of stigma associated with the disorder, but also a desire to not be defined by illness and just be seen as an “ordinary” 21 year old, who doesn’t have a very complex medical and emotional past, is really strong in me. The reality is, even though there is no such thing as an “ordinary” 21 year old, if there was I would be about as far from it as possible. That doesn’t have to be a bad thing or define me, or be sad and reason to “pity” me.

But coming to terms with that and knowing how to broach those conversations…. I am at the very beginning of that part of this journey, and I have been diagnosed for almost 20% of my life. So the fact that people are now looking to me and asking about how I navigate social life with FND as a young adult… the honest answer is letting shame about the diagnosis, fear of people’s perceptions, and a desire to separate my identity from it has historically guided it up until literally early December 2024 (and the interview was filmed a week later). So that’s my long preface, that I am at the beginning of owning the social life and FND part, letting the two mix, but that doesn’t mean FND hasn’t impacted my social life.

I was diagnosed in October/November 2020, right in the height of the pandemic and virtual learning in Seattle. Honestly, it was a blessing to be diagnosed when I was. The previous year, 2019, I spent nearly 8 months in the hospital due to a heart condition, and it was so much harder to be sick when everyone else was navigating normal life… I had to drop 2 classes, and took the other 4 as self guided from the hospital, which took a lot of fighting with my school to not un-enroll me when I attended zero in person classes for the entirety of second semester. I missed theater performances, swim meets, birthday parties. It felt so much more unfair, lonely, and impactful to be hospitalized then. My close friends were amazing, visiting on the weekends, texting me updates, and even bringing me hilarious and thoughtful gifts that would keep my spirits up until the next weekend. But I missed going to school and while I appreciated updates, resented not experiencing them firsthand. It was lonely and isolating.

But in 2020, I experienced none of that. My school didn’t know I was in the hospital or sick once discharged, because I could attend class on teams and used school as a distraction and maintained grades despite 15+ seizures a day. Friends could call me, and they knew I was sick, but it didn’t mean I saw them less -they could honestly be more of a support and distraction, rather than something I went through alone. Choir, theater, even swim team, all met on zoom. If I was having a bad day, I could log on and keep my camera off. Maybe this enabled the secrecy about the diagnosis, but it also kept me going, and maintained my normalcy -something many FND providers always emphasize as important in recovery, but would have been impossible for me without everything be virtual. It also meant my parents were working remotely and could support me more. Importantly, it enabled me could go out of state for treatment. At the time, there was literally only one FND provider in the country willing to take a pediatric (17 year old) patient. Since my parents were working remotely, it was much more financially feasible -and it meant my brother could come with me, because he was also doing remote school and extracurriculars. All this to say, initially my social and academic life was pretty minimally impacted by FND initially, thanks to Covid.

In fall of 2021, in person school started again -but I was much less symptomatic due to making substantial improvement in treatment the previous year. There were subtle difference between me and my peers, but they were very subtle. For example, I was co-captain of the girls swim team. Swimming and seizures was something that was took a lot of convincing for all of my providers to sign off on, but I rightfully pushed for it, because swimming was incredibly regulating for my body and mind -and also an important community to me since the age of 6. My highschool team meant a lot to me, and my best memories of my highschool pre-Covid was my freshman year season and the support of the girls on the team. My two best friends were also on the team. I wasn’t going to not do it because I was very rarely having seizures that I could usually anticipate or delay until safe, and were usually in acute stress or illness, not a random swim practice. My treatment team conceded it would be more harmful for me to not be able to participate with the stipulation that my parents be at every practice watching me individually (as lifeguards were responsible for the entire team). I eagerly accepted the compromise but didn’t anticipate having to explain why my parents were at every practice, or were the only people allowed at meets (Covid restrictions). I ended up saying something like “oh yeah, I have seizures, so they just keep an eye on me” and immediately changing the subject when one swimmer asked. Overall, very little social impact, but situations like these were difficult to navigate.

Then I went to university. I started 8 months seizure free and that unfortunately was sustained for less than 2 weeks. This is where the true social impact of having seizures became incredibly apparent. I did a study abroad program my first semester of university with about 45 other students (again, truly trying to distance from myself from FND and high-school experience, and it backfired pretty hard). Having a seizure, 2 weeks into a program with a small group of young adults, who were all navigating an incredible amount of change, stress, and social pressure, none of whom knew me really as a person, was pretty catastrophic socially. I was excluded from most group social events very explicitly, some people posted videos about the the exorcism and compared it to me. It was very, very lonely, especially the first couple of months.

Here’s where I feel a need to say something: I actually understand where some of the people came from (those who were scared to hang out with me). We were 18, and for the first time in our lives, there was no “parent” who could rescue us in an emergency because they were 10 minutes away, or really tell us what to do. They were navigating their own difficulties learning to live independently. If we were out hanging out, and I had a seizure -that is terrifying to someone who has never seen one or knows how to manage one, regardless of the fact that I had emphasized the lack of risk to myself during one, and that it was OK to just wait it out. It is scary and not what they had the capacity or wanted to risk managing. I actually experienced this when my friend (without an epilepsy diagnosis) unexpectedly had an epileptic seizure and fell into the middle of a road with me. Despite working with people with epilepsy in an EMU, having seizures myself, knowing seizure first aid, it was terrifying and definitely emotionally impactful, and I can’t imagine their experience at 18 without any of that context. I understand that that’s not personal to me -but rather the reality of the situation. But the impact was personal to me, and even if I understand where that dynamic comes from -it doesn’t make it feel it less lonely or horrible.

But in the end, it almost was a blessing. After many weeks of very hard nights and weekends, pretty explicit social outcasting, and phone calls home questioning if I ever could live independently or do what I wanted, I found people who could care less if I had seizures and are some of the kindest people I’ve ever met. It almost was a “filter” of people who weren’t kind or at the very least, in a position to be friends with someone with health issues. The people who ended up being my friends are hilarious, kind, and saw me as someone impacted by seizures but not defined by them. When the program abroad ended and we integrated into the bigger university in the US, I had my people. They were “my people” the entire time I was there, still are some of my closest friends from a far, and three of them becoming my roommates and truly my best friends. Still, my FND was something that remained pretty personal and private -despite them knowing I had seizures, helping me through them, etc.

When I entered my program this fall in 2024, nothing about my approach to my social life and FND not mixing had changed. I NEVER hid that I had seizures with someone who I knew I would be interacting with 1:1 frequently, because that is not a surprise any one wants, and always explained an ideal seizure plan for myself, but gave little elaboration. It was rare for me to mention it after this initial very business, check box style conversation. It came up sometimes if someone came into my apartment and asked why I had an emergency pull cord, but again the answer was honest but limited to the least amount of information I could possibly give.

I developed really close friendships. People I trusted immensely, was silly with, vulnerable with about other things, was trusted by, etc. Unfortunately, despite my symptoms being well managed most of the term -I did have a seizure around one of my best friends. It wasn’t a surprise in that he knew I had seizures, but it was understandably very scary and shocking to witness. He was incredibly kind and supportive, especially when I was expecting that he might not want to hang out with me again, and he yelled at me for thinking he was mean enough to have such a thought when I revealed why I had been more withdrawn. A couple of days later asked something no one else had, in the four years I had been diagnosed, “What is FND? What is a functional seizure? How does it affect you?”

Perhaps it was because we were pharmacy students and it was more of an innate medical curiosity, or maybe he was braver than others and asked what others had been scared to ask. He had probably googled it and was confused with reconciling the information he had seen on the internet, who he perceived me to be, and the seizure he had witnessed, and wanted clarification from me because those things didn’t make sense. At this point, it was almost midnight and we both had lab the next day at 8 am, and we were on the phone -I knew, for the first time since my diagnosis, I wanted to properly explain it -or at least my experience of it, and this was not the time or place. I said something along the lines of… “that’s a longer conversation, can we have it in In person when we have more time? I promise I will explain it.” He kindly agreed, probably a little surprised.

In true Teja fashion, I wanted to do it right, so I definitely overthought it. I had done a presentation on what FND was, current research on it, etc. to medical students as a like introduction to the disorder and current understanding of it. It didn’t feel appropriate for my relationship with this friend, although he’s incredibly smart and likely would have understood it -he was asking about the disorder, but not an academic lesson as part of his healthcare education program, in his friend. I did decide doing a presentation would help me structure the conversation and not let me get swept up and lose track of the message I wanted to bring home (which I didn’t know what was yet, but knew a presentation would likely increase articulating it once I decided on it).

I spent a lot of time on this presentation. I tried to balance a lot of things:

-What is FND understood to be? Honesty about the current science and understanding. Given we were both in pharmacy school and physiology nerds, I knew he would have a lot more context and bandwidth for psychology and neurology research and intersection, but I didn’t want that to be the sole focus. He didn’t ask for an academic lecture to pass an exam, he was asking because one of his friends had it, and it impacted their life. Mechanism, etiology, statistics, could give some framing or context, but they were not a priority at all… I mostly used them to frame my experience of the disorder, and my diagnosis story and my timeline with it, how it’s impacted my life.

- what is my experience of the disorder? I started with when and how I was diagnosed, and kind of walked through a timeline of how it has influenced my life and even brought me to me the UK for pharmacy school. Symptoms I had experienced, correlating factors I attributed to what potentially contributed to me developing it, how I had learned to live with it. It was pretty personal. I also talked about my work, and how important it was to me, and the meaning it brought to my life to work with other young adults with FND and see progress -how that was one of the main sources of purpose in my life at the moment, which surprised him given how I never talked about it.

-Most of all… I didn’t want this to be a sad conversation. I wanted to reflect how hard my experience with FND was but not have the takeaway be that it has defined who I am, that I am a victim to it, or for him to view me with any form of pity. It’s hard to balance that, to be vulnerable and honest that I have experienced a lot of suffering because of FND, but honestly, it’s ultimately made me a much much stronger person, more defined in my sense of true self, helped me recognize I would benefit from trauma therapy, brought me closer to people like my parents, given me purpose in m current job outside of school, and solidified to me that I can overcome hard things. None of that makes the suffering go away, but I didn’t want suffering to be the sole takeaway. I also didn’t want to bombard him all at once with a lot of pretty heavy things, so there were a lot of memes and jokes, and I kept it relevant to our friendship (IE referencing inside jokes or pretending he was my student and quizzing him with the question style of our program, or referencing concepts we had learned about in our own program with eye rolls from him at mentions of “the value of a multidisciplinary team”).

It was scary to make and scarier to give. But his reaction was so typical of him that I knew it was the right decision and that it hadn’t permanently altered our relationship in a negative way. He asked a few questions, then said “he wanted to dig into these weird neuropsych niche on his own” in his own research, laughed at my use of memes, asked for an interpretative dance (that’s how we like to study and explain scientific concepts through charades, so he was disappointed there wasn’t one in the power point), and then basically asked if I could still watch the TV show we were planning on watching that evening. Since, I’ve been much more honest with him. If he asks how I am doing, I am more likely to say “I really wish I had slept more last night and my body is feeling it”, or randomly text him about something that made me happy (or angry) at work. But none of it defines the relationship, it just allows me to be more authentic in it.

Part of my assignment for this write up/reflection (which has now turned into a super long personal reflection more so than actionable advice, I apologize), was to reflect on “how to explain FND to someone and when to do that?”

But here’s the conclusion I’ve come to over two weeks of procrastinating writing this (an indicator that this was likely going to be emotionally challenging and I was avoiding it more so than the other topics)...

There’s no universal answer. Clinicians can’t even currently come up with a universal definition of the pathology of FND- every researcher/provider uses a different definition in their publication or framing to the patient. How can I, as a patient, then come up with a definition true for all patients experience of the disorder? I have my thoughts on the explanation scientifically based on research, but ultimately… the diagnosis and pathology is incredibly broad, and the experience of it is so heterogeneous, even within young adult patients with my exact subtype of functional seizures. What it means to us, how we come to understand it, how it presents, in my mind is so individual that there will be no universal definition that could explain it in an interpersonal relationship. Perhaps as a broader neuropsychiatric concept, because by nature of its pathology, it presents differently in every patient, but a friend or family member doesn’t care about the pathology, they care about the individual and its impact on them.

That’s perhaps why I have skirted this conversation for so long… it’s a deeply vulnerable and personal thing to acknowledge that FND has impacted me. I am pretty stubborn about not letting it limit me. I don’t want it to define me and have fought incredibly hard to not be as symptomatic as I once was… but the reality is, it has fundamentally shaped my identity, my path in life, for both better and worse, and not disclosing that to loved ones -like truly valued relationships, shows a lack of faith in their ability to love me for who I am, and part of having the courage to disclose it is self love and confidence that because it is part of who I am, it is part of why they love me.

As for when that conversation happens… that is a different story. This is a vulnerable conversation, for the reasons just stated. You don’t owe anyone any form of medical or emotional explanation outside of what will keep you safe in the event of an FND symptom and not shock someone, so this is a conversation I would personally not have, at least to the extent I had it with this friend, until a clear genuine trust and relationship had formed. Only you will know when it feels like that level of trust has been achieved -it will probably be different for everyone.

The conversation will also be different with every person. I told my flatmates, people who have been incredibly kind and more than proven their trust and valued relationship, that I did this with my friend, and asked if they would be willing for me to make a presentation for them. But the presentation will be unique to them, not the same. They were eager. One of them asked if they could do the same for the group for their diabetes. It meant a lot that they would share with me, since I know their journey with diabetes has been anything but easy, and I all of a sudden understood even more why this conversation should happen with people you care about.

I guess all this to say… the impact of having FND as a young adult on me personally has solidified to me that it will be clear who true friends are, and I need to trust that they will love me for who I am -including the ways in which FND has impacted me, and honestly, the reason it has taken so long for me share it is likely more of a testament to how difficult it is to come to internal acceptance of the disorder and how it has impacted me.

There will always be people who weaponize it, and make your life harder because of it, only seeing the bad pieces part of it and letting that define their entire perception of you. There may be people who go as far as to post videos about you being an exorcist, who refuse to interact with you or invite you to events because of your seizures. That sucks. It’s unfair and it’s OK to be angry. To want to scream and throw things and question why they can’t see you for you. But you know who you are. It isn’t an exorcist, and is someone who should be there. You have people in your life who you love, do not deny yourself the opportunity to show this part of yourself… because they will see the nuance and complexity, and that it is not all you are, it is not reason to pity you, and it is instead a part of your life that they want to support you through the hard moments and celebrate the good.

I guess this was longer and much less practical than previous reflections, but certainly the most honest. FND isn’t easy. It’s OK for it to take time to share with people other than providers… but it’s also something I am incredibly grateful I am starting to do. Will I mess it up in the future or will it go not as well? I am sure. But it will probably also get less scary and I might even be able to do it without a PowerPoint, but that’s in the far distant future.

Watch FULL video interview here

Connect with Teja: [email protected]

Ready to connect? Contact me now :)

Are you ready to engage in the Awaken Level 1 course? Ready to continue moving upwards on the ladder of Functional Awakening?

Would you like a 30’ personalized and free introductory conversation? Request it by completing the anonymous Self-Assessment questionnaire: Holocene Method: The Health of the 4 Universal Bodies/Neuronal Networks.

Disclaimer: Dr. Velazquez has not had the chance to review the above article for scientific accuracy, nor she is endorsing any type of opinion, comment, suggestion, product or treatment possibly mentioned. You are the sole responsible for the interpretation of the data shared by our Patient Collaborators or Personal Experts. Whenever in doubt you can contact directly the person who wrote this Blog Post article and/or you can report it to Science & Shamanism, LLC, Dr. Velazquez and/or her designees. We will always try to help! Within the limitations of our human existence and capabilities, considering scarce time and high workload.

Join our Mailing list!

New inspiration and information delivered to your inbox.

We will never sell your information, for any reason.